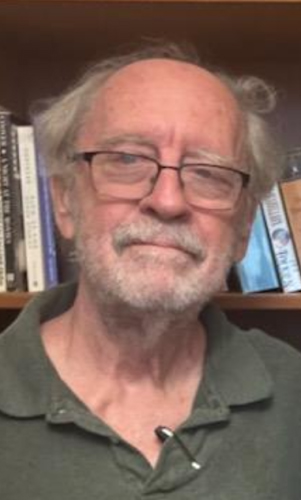

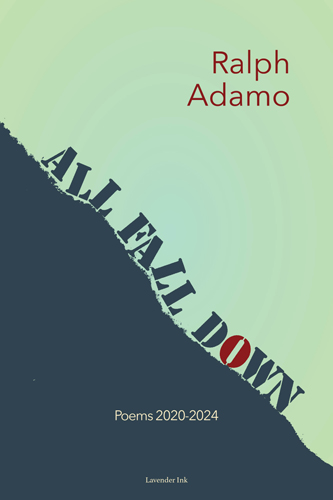

In his 10th collection, composed during a time of disruption and conflict, Ralph Adamo explores humanity itself by focusing our hardest questions and most troubling understandings through his own experience, memory and imagination. He also addresses or invokes a myriad of you’s to broaden this investigation. While the poems are ambitious, the words they are cast in reman plainly conversational, with occasional bursts of more exotic and lyrical language. And while the consciousness of death and its propulsive influence on our lives informs many of them, livelier intentions appear as well, in poems that search out the mysteries behind the simplest aspects of our daily experiences. The moon is here, the dog, the cats, the beloveds, the grind, the ecstasies, and the promises and dreams that extend our lives into the future. Ultimately, the poems reflect a darkness in which hope might still prevail. Adamo suggests these poems inhabit a new category, for readers who want such classifications. He writes, ‘Post-confessional poetry, which mine seems to be, isn’t about a whole life or sustained feelings or any stable series of moments. Rather it carries the shards of thought -- feelings that might vanish as quickly as they appear, passing fragments of brief durations captured imperfectly in language as if somehow permanent.’

I like poems that explore complexity. And ambiguity.

Often while appearing to speak plainly.

Nothing is more than one thing.

While humbly appreciating the writers who have blurbed my other books (noting that my first five have no blurbs, had sought none), and standing by any blurbs I have written, this practice seems unavailing (for me at least), if endearing. So I will write my own, and this is it: I am happy to think anyone has picked this book up, excited that we might meet in its pages, touched at the thought of you spending this time with me.

About the work itself, I believe that the imagined selves herein could be a mirror, might even be galvanizing, maybe sometimes transcending the petty materials of the ordinary life we most of us live. The book is full of you, and you are no one, someone, everyone, me, and, of course, yourself. Many bad decisions and much exceptional luck have led me here. You?

There are so many words competing for our attention, so many images dancing in front of us, such eagerness everywhere to be seen—even to perform—in the universe of the poem and, of course, beyond it.

Poetry these days is a lava flow of the thing and the feeling. If there are ideas, they are ephemeral and if there are stories, they carry the seed of lies. Voices desire to become music.

Post-confessional poetry, which mine seems to be, isn’t about a whole life or sustained feelings or any stable series of moments. Rather it carries the shards of thought—feelings that might vanish as quickly as they appear, passing fragments of brief durations captured imperfectly in language as if somehow permanent.

With suffering in the world so acute, so pervasive, poetry might seem like a luxury. But the example of many poets throughout history, writing as though their lives depended on getting the words on the page right, gives us more cause to see it as a necessity.

—RA