The Creole praline arrived in New Orleans with the migration of formerly enslaved people fleeing Louisiana plantations after the Civil War. Black women street vendors made a livelihood by selling a range of homemade foods, including pralines, to Black dockworkers and passersby. The praline offered a path to financial independence, and even its ingredients spoke of a history of Black ingenuity: an enslaved horticulturist played a key role in domesticating the pecan and creating the grafted tree that would form the basis of Louisiana’s pecan orchards.

By the 1880s, however, white New Orleans writers such as Grace King and Henry Castellanos had begun to recast the history of the praline in a nostalgic mode that harkened back to the prewar South. In their telling, the praline was brought to New Orleans by an aristocratic refugee of the French Revolution. Black street vendors were depicted not as innovative entrepreneurs but as loyal servants still faithful to their former enslavers. The rise of cultivated, shelled, and cheaply bought pecans―as opposed to the foraged pecans that early praline sellers had depended on―allowed better-resourced white women to move into the praline-selling market, especially as tourism emerged as a key New Orleans industry after the 1910s.

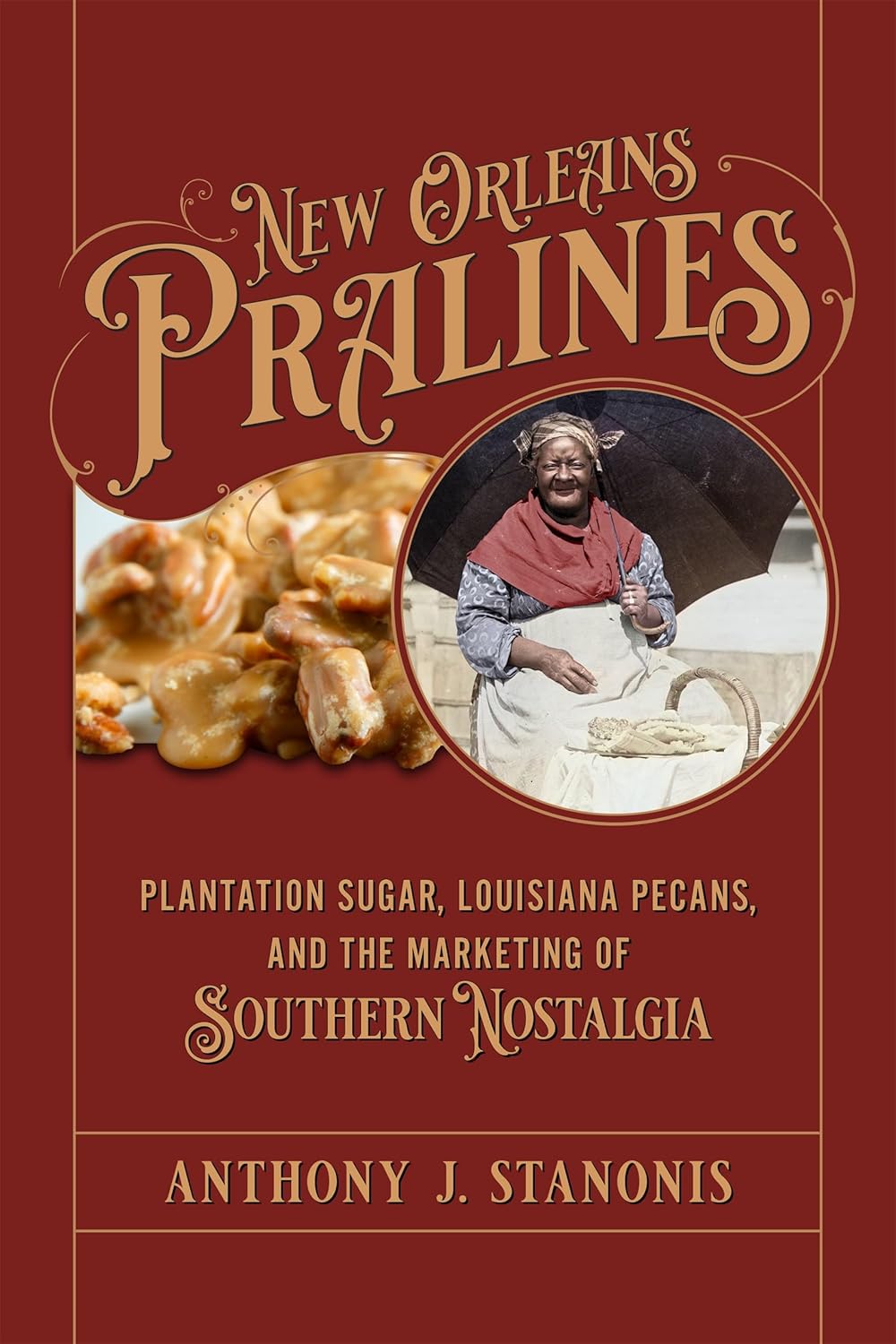

Indeed, the praline became central to the marketing of New Orleans. Conventions often hired Black women to play the “praline mammy” role for out-of-towners, while stores sold pralines with mammy imagery, in boxes designed to look like cotton bales. After World War II, pralines went national with items like praline-flavored ice cream (1950s) and praline liqueur (1980s). Yet as the civil rights struggle persisted, the imagery of the praline mammy was recognized as an offensive caricature.

As it uncovers the history of a sweet dessert made of sugar and pecans, New Orleans Pralines tells a fascinating story of Black entrepreneurship, toxic white nostalgia, and the rise of tourism in the Crescent City.